Military service members who have returned from theaters of war are at increased risk of mental health problems. But few studies have examined the physical effects that war-zone related stress may have on the structure of the brain.

A new study led by investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham health care system, investigates microstructural changes in the limbic and paralimbic gray matter regions of the brain—areas that control basic emotions and drives.

The team analyzed diffusion-weighted MRI scans from 168 male veterans who had participated in the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS) study, which took place in 2010 to 2014 at the Veterans Affair Rehabilitation Research and Development TBI National Network Research Center.

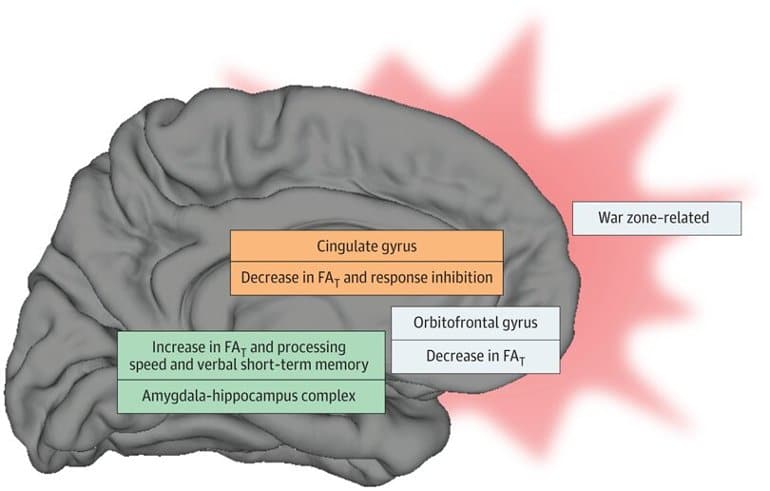

The team found that war-zone related stress was associated with alterations of the limbic gray matter microstructure, independent of a diagnosis of a mental health disorder or mild traumatic injury. These structural alterations were, in turn, associated with cognitive functioning, including impaired response inhibition as well as improved verbal short-term memory and processing speed.

“These findings suggest that war zone-related stress may lead to microstructure alterations in the brain,” said corresponding author Inga K. Koerte, MD, of the Psychiatry Neuroimaging Laboratory in the Brigham’s Department of Psychiatry.

“These changes may underlie the deleterious outcomes of war zone-related stress on brain health. Given these findings, military service members may benefit from early therapeutic interventions following deployment.”

Source: https://www.brighamandwomens.org/

Journal article: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2796359

Image is in the public domain

Image: War zone–related stress was associated with decreased fractional anisotropy of tissue (FAT) in cingulate and orbitofrontal cortex, as well as increased FAT in the amygdala-hippocampus complex. Limbic gray matter FAT measures were further associated with cognitive function (ie, impaired response inhibition as well as improved verbal short-term memory and processing speed). Taken together with the current literature on functional imaging in posttraumatic stress disorder, we propose that the observed diffusion alterations may result from a functional shift from frontolimbic toward mesial temporal structures (shift of functional demand from cingulate and orbitofrontal regions toward mesial temporal regions). Credit: The researchers

September 29, 2022 at 1:48 am

A lot of wisdom here……..

LikeLike